Something has got jammed in the works of global logistics chains. Failure or inadequate monitoring of container shipping trends has exposed the port community to disproportionate cost increases and deteriorating quality of services. Likewise, institutional agreements on competition in the sector, including the so-called Consortia Block Exemption Regulation, which, in April 2020, the European Commission decided to renew for an additional four years, have also partly contributed to this phenomenon.

The International Transport Forum has gone on the attack. In a report published a few days ago, the OECD think tank shone a spotlight on how big carriers have been acting over the last few years and the failure of antitrust authorities to cope with monitoring situations of dominant abuse and anti-competitive practices.

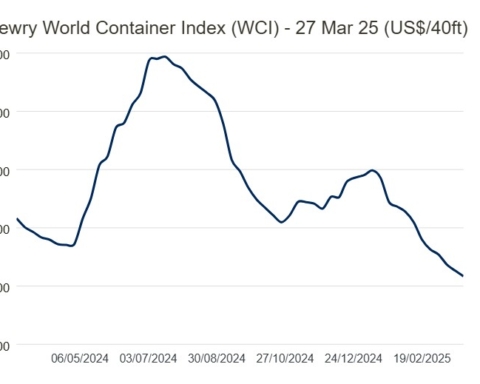

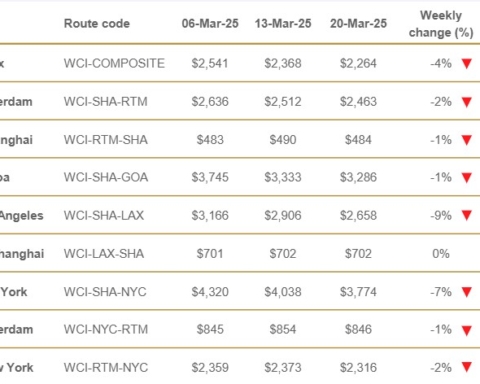

The report points out that the cost of transporting containers has increased significantly since the beginning of 2020; rates on the spot market have practically increased sixfold, while those on long-term contracts have tripled.

These figures are dramatic. According to the ITF, they do not give a complete idea of the real costs associated with container transportation that shippers have had to bear during this time period i.e. the extra costs charged by big carriers for container detentions in and out of port terminals beyond the terminal free time period. The detentions & demurrage fees, as pointed out by X Change, increased on average by 38% from 2020 to 2021, before falling in 2022.

Over the same period, the reliability of global container lines’ schedules fell from 65% to 34%, which, according to the ITF, means that two out of three vessels arrive in port at least one day late. In addition, the so-called blank sailing phenomena has also increased. To compensate for the reduced demand for goods and services during the pandemic period, shipping lines have increasingly resorted to cancelling sailings in their scheduled liner services, skipping ports or reducing the number of calls, thereby putting new pressure on global supply chains.

The International Transport Forum points out how the amount of time ships spend in ports in the People’s Republic of China and the United States has virtually doubled since the early 2020s, while in Europe it has increased by almost 15%.

Together with Covid19-related manpower shortages, these events have undermined just-in-time business and logistics models, creating major disruptions to supply chains.

According to the ITF, in Europe freight forwarders and shippers are facing exponential increases in ocean freight rates to and from Europe and increasing difficulties in booking slots on board ship.

In addition, shipping lines have adopted less than fair business practices to shift their fleet capacity to more profitable routes, such as the transpacific one, in order to meet the growing demand for consumer goods in the U.S., thus leaving other routes unprotected and further inconveniencing shippers.

The ITF says public policies have facilitated this intolerable scenario. According to the OECD think tank, regulatory authorities have allowed carriers to use cooperative agreements to jointly manage fleet capacity and condition markets. Moreover, skyrocketing rates have led shipping lines to accrue mega operating profits, hitting an astronomical $160 billion in 2021.

The extra revenue has been used by companies to vertically integrate the logistics chain and create problems for freight forwarders. The ITF considers vertical integration to be discriminatory because it is perpetrated by those who, unlike other logistics operators, benefit from an exemption from the normal rules of competition and use their profits to compete in other sectors that have no such exemption.

In short, the situation is becoming unsustainable. The ITF is therefore calling on governments to strengthen controls to assess the real degree of competition in container transport, insisting that competition authorities strengthen cross-border cooperation, so their actions are interdependent.

The International Transport Forum is pointing its finger at consortia, i.e. occasional joint-ventures between two or more big carriers even operating outside the same alliance, through which, it becomes possible to position ships along different routes and thus control fleet capacity.

According to the ITF, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which the various Regulatory bodies have so far used to assess the degree of concentration of the market share, does not take into account the full spectrum of joint ventures set up between shipping companies and allowed under the block exemption and other antitrust immunity provisions.

If such consortia agreements (inter-Alliance consortia) were subjected to the measurement system, the degree of concentration recorded on the transatlantic route, for example, would not be only moderate but, indeed, very high (“higly concentrated”).

The ITF then recommends that a series of measures be put in place to make detention & demurrage fees more transparent by putting the onus on carriers to justify them

According to the International Transport Forum, detention and demurrage fees levied on shippers to regulate transport flows at ports should be made more effective by ensuring that they are related to the costs incurred. In addition, such fees should only be charged if shippers and forwarders are directly responsible for the non-delivery or delayed redelivery of containers.

As for vertical logistics, the ITF is calling on regulators to ensure transparent and fair competition in port and logistics markets currently dominated by carriers specialized in container transportation.

Finally, the International Transport Forum points out how the fee for using public port facilities is currently low. Carriers contribute only 4% of the cost of financing and maintaining ports facilities. According to the report, governments should recover a greater share of infrastructure costs from carriers through fees or additional charges.

Translation by Giles Foster